By: Greg Whittaker

By: Greg Whittaker

Animal Husbandry Manager at Moody Gardens

As a boy growing up on a farm in upstate New York my world didn’t include sharks.

Unlike many of my colleagues that had aspirations of becoming Marine Biologists, I had no such lifelong dreams. I was content to spend my free time fishing in our pond, hunting in our woods, swimming on my high school team and generally being a free-spirited rural American kid.

I was steered into Marine Biology by my uncle who touted the field as a wide open frontier with high-wage job opportunities and since it involved both the inherent study of biology and water I thought, “Sounds cool.”

So I packed up what I assumed I would need and moved to Galveston to attend one of the top ranked Marine Biology programs in the nation, although secretly I was more excited about living on an island on the Gulf of Mexico. Most aspects of island life were much different than what I was used to, but there was fishing.

Fortunately for me and the local sharks, my undersized tackle and lack of local fishing knowledge ended most interactions with a speedy “catch and release.” As my conservation ethos and fishing experience both grew, these catch and release episodes were based more on my judgment and less on their toothy grins.

The three sharks that I’ve caught and kept have all ended up in my kitchen as my mom always insisted if I killed something I ate it. Shark meat can be prepared to taste very good, but there are several important steps from the moment you catch it to how you cook it that can change the final taste. I didn’t follow any of these steps and as a result, my fishing activities no longer result in sharks coming home for the dinner table.

I had seen JAWS, and the increasingly ridiculous sequels, and I suppose my observations of the natural world kept me from falling prey to the anti-shark hysteria that those movies ingrained in so many viewers. I did gain just enough fear to feel uneasy during all those late night beach parties when we ventured out past the sandbars into the dark unknown.

I’ve come to appreciate that is a normal healthy phobia that we all should have as we’re entering the predators’ world at dinnertime. Many sharks rely on a balance of sight, smell and sensitive electrical sensing to find their food, and the twilight periods before sunrise and after sunset offer them the perfect competitive advantage in locating prey.

I find myself repeating the same speech every couple of years when we’re asked to comment on a local shark bite incident; “avoid swimming at dusk and dawn, always have a buddy to help out if there is a problem and avoid swimming where large schools of bait fish are found.”

Having worked with sharks in the aquarium environment for the last 24 years, I have a great appreciation for their place in the natural world. They are ancient and perfect in their ability to survive in so many specialized niches. They found their various jobs millions of years ago and continue to adapt to changes in the environment and pressures placed on them. Like apex predators in every ecosystem in the world, sharks are losing the battle with humans; habitat destruction, food web interruption, pollution, trophy hunting and simple misinformation based persecution. They are not the malicious killers portrayed in that 1975 movie that is perhaps responsible for many species’ spiraling populations today.

I still go fishing whenever I can get the time, and I still try to catch sharks as they are very worthy adversaries in that primal tug of war. Pictures are taken and care is given to efficiently release them so they can continue to do their job in the world around me.

The ones we keep are destined to become part of our living collection of ambassadors, maintained in as natural an environment as we can achieve so that our guests can come to see and appreciate them for the beautiful creatures they are. Maybe, if we’re successful and luck is on our side, we might even inspire a growing army of conservation minded individuals to re-evaluate our place in the natural world and take steps to ensure that all species have a future.

The ones we keep are destined to become part of our living collection of ambassadors, maintained in as natural an environment as we can achieve so that our guests can come to see and appreciate them for the beautiful creatures they are. Maybe, if we’re successful and luck is on our side, we might even inspire a growing army of conservation minded individuals to re-evaluate our place in the natural world and take steps to ensure that all species have a future.

Sharks’ teeth are adapted for what they eat. Sharks like the great white and tiger shark have triangular teeth with jagged edges. This keeps hold of larger fish and animals, tear chunks of meat or slice through a turtle’s shell. A sand tiger’s teeth, on the other hand, are long and narrow which make them look frightening, but in fact these types of sharks are not very aggressive. The shape of their teeth is ideal for grabbing a hold of prey. However, the whale shark has very small teeth and it’s not used for biting because they simply filter their food.

Sharks’ teeth are adapted for what they eat. Sharks like the great white and tiger shark have triangular teeth with jagged edges. This keeps hold of larger fish and animals, tear chunks of meat or slice through a turtle’s shell. A sand tiger’s teeth, on the other hand, are long and narrow which make them look frightening, but in fact these types of sharks are not very aggressive. The shape of their teeth is ideal for grabbing a hold of prey. However, the whale shark has very small teeth and it’s not used for biting because they simply filter their food. Coloration and patterns play an important role in identifying a shark. Their special marks allow them to camouflage perfectly into their environment. Mako sharks, for example, inhabit tropical and offshore water and are normally a bluish color. On the other hand, the nurse shark has a tan pigmentation ideal for hiding on the ocean’s floor. Tiger sharks can be identified by their stripes and leopard sharks for their spots.

Coloration and patterns play an important role in identifying a shark. Their special marks allow them to camouflage perfectly into their environment. Mako sharks, for example, inhabit tropical and offshore water and are normally a bluish color. On the other hand, the nurse shark has a tan pigmentation ideal for hiding on the ocean’s floor. Tiger sharks can be identified by their stripes and leopard sharks for their spots.

In early 1999 I found myself in Taiji, Japan working on a marine mammal acquisition for the Beijing Aquarium. The conservation ethics surrounding “The Cove” are another story deserving its own chapter at another time. While we were working at a Dolphin encounter resort on the outskirts of Taiji, we were staying in a fishing community just to the north called Katsuura. Every day we drove past the waterfront in Katsuura through the bustle of activity around the fishing markets. On one of my few days off, I visited the market to see what was being caught and auctioned. The sheer number of top level predator fishes that were laid out in organized stacks in the football-field-sized warehouse space was amazing. Tuna, mackerel, billfish and ocean sunfish made up the bulk of the daily catch. There were also several piles of shark fins stacked 4’ high and spreading over perhaps a 12’ diameter area. I couldn’t locate any shark bodies in the entire market area, just three or four large heaps of fins.

In early 1999 I found myself in Taiji, Japan working on a marine mammal acquisition for the Beijing Aquarium. The conservation ethics surrounding “The Cove” are another story deserving its own chapter at another time. While we were working at a Dolphin encounter resort on the outskirts of Taiji, we were staying in a fishing community just to the north called Katsuura. Every day we drove past the waterfront in Katsuura through the bustle of activity around the fishing markets. On one of my few days off, I visited the market to see what was being caught and auctioned. The sheer number of top level predator fishes that were laid out in organized stacks in the football-field-sized warehouse space was amazing. Tuna, mackerel, billfish and ocean sunfish made up the bulk of the daily catch. There were also several piles of shark fins stacked 4’ high and spreading over perhaps a 12’ diameter area. I couldn’t locate any shark bodies in the entire market area, just three or four large heaps of fins.

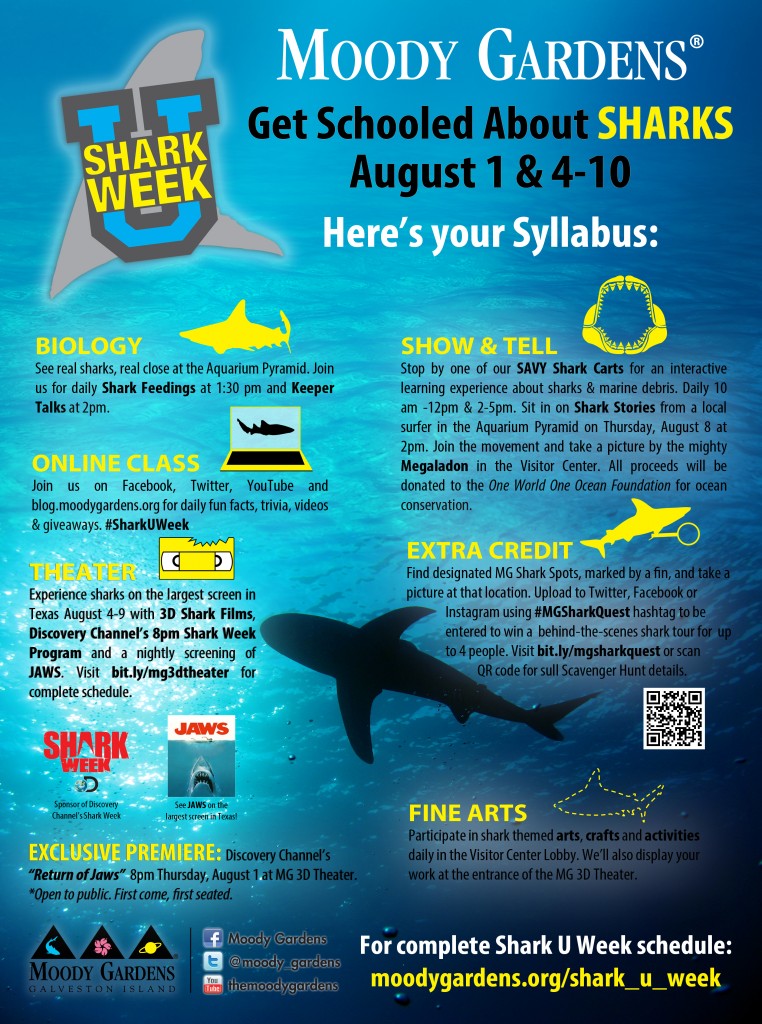

Working in the zoo and aquarium industry offers a lot of perks. That’s because we get to work with some of the coolest animals in the world.

Working in the zoo and aquarium industry offers a lot of perks. That’s because we get to work with some of the coolest animals in the world.